COLUMN: Game, Set, Gone: Why It’s Time to Say Goodbye to Professional Tennis in Montreal

ColumnThursday, 24 July 2025 at 20:29

In two days, the world’s best women’s tennis players will touch down in Montreal for the Omnium Banque Nationale, a marquee WTA 1000 event that’s expanding from one to two weeks this year. They’ll smile for cameras, play for packed crowds, and do their best to ignore a truth that tennis insiders and fans here have known for years: Montreal’s Stade IGA is no longer fit to host a tournament of this magnitude.

Not one, but two articles in Radio-Canada have tried to sound the alarm, calling the venue the worst of any top-tier WTA 1000 tournament on the calendar. As someone who lives steps from the grounds, I’ll go one further: it doesn’t even meet the standard of an ATP or WTA 500 event. Our facility—and the experience for fans, players, and staff—has become, through time, decay, and government and organizational apathy, an embarrassing outlier in the global tennis ecosystem.

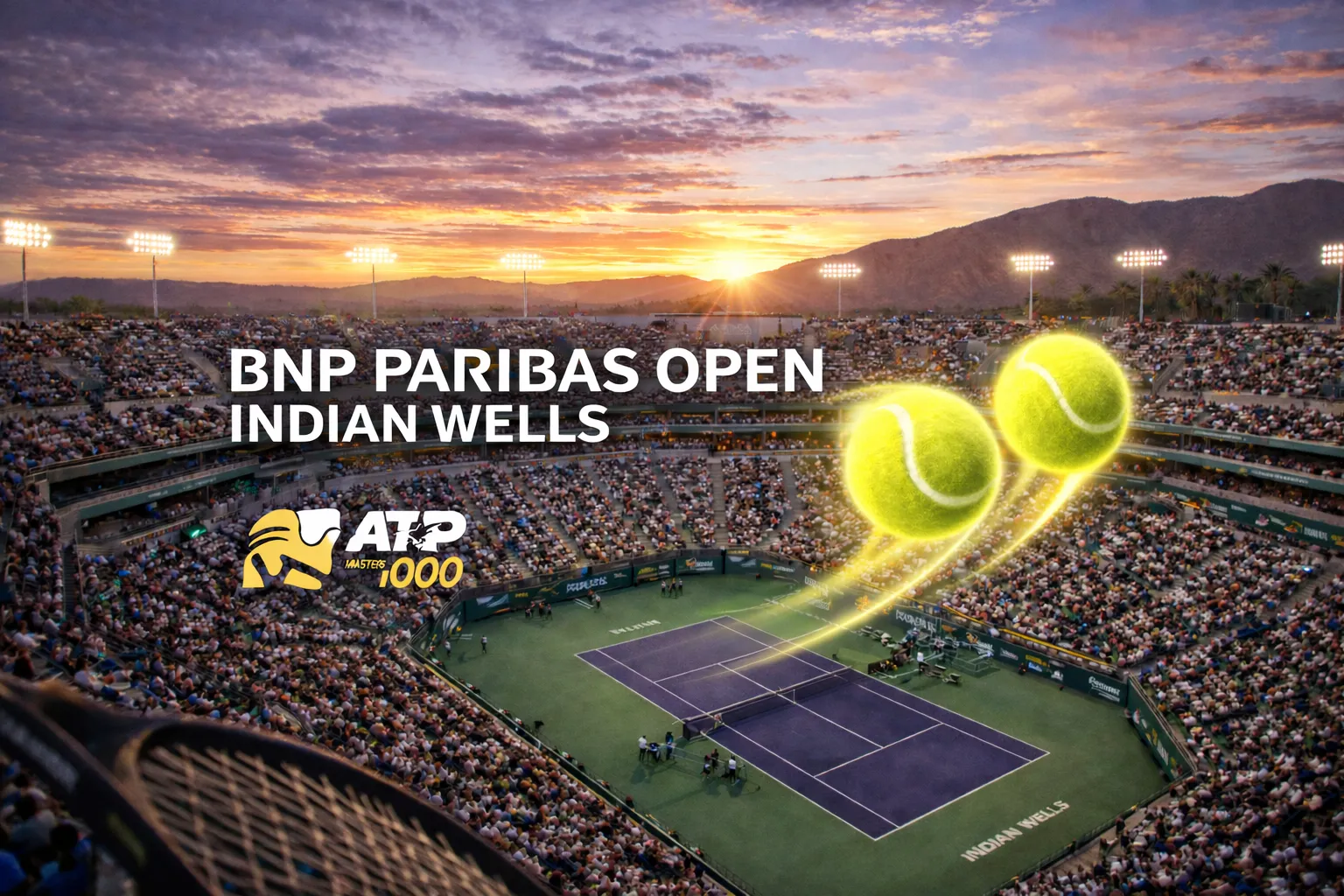

This isn’t just about cracked concrete, cramped locker rooms, or the logistical indignity of shuttling top-seeded players through a maze of chain-link fences to get them to court. This is about a venue that has fallen catastrophically behind its international peers. Want to know what a true WTA 1000 looks like? Visit Indian Wells. Or Madrid. Or Rome. These places hum with energy and efficiency. By contrast, Stade IGA feels like a rickety holdover from a bygone era—charming, perhaps, if you’re nostalgic for the 1970s, but wholly inadequate in 2025. Or look at Cincinnati, which has committed a whopping $260 million to bring its venue up to and beyond par. The amount committed in Montreal? Zero. We’re merely thinking about it.

What’s worse is that Tennis Canada and city officials aren’t just confronting an infrastructure problem—they’re dealing with a geographic impossibility. Unlike many of the world’s top tournaments—Indian Wells, Miami, even Toronto—Stade IGA is jammed into the middle of a bustling, mixed-use urban neighborhood. In 2020, during the pandemic, the area was uncharacteristically quiet: no office commuters, no buzzing cafés, no street traffic. It was a logistical dream for a major stadium renovation.

Read also

That moment has long passed. The neighborhood is absolutely booming. Offices are full. Streets are choked with traffic. Street parking is a fantasy. The idea of shutting this area down for a year—or more—to carry out the estimated $300 million in renovations needed to modernize the complex is laughable. Not just implausible—impossible.

And I say this as someone who would love to see world-class tennis continue here. I live in the neighborhood. I walk past the venue several times each day and, as a nationally ranked senior player, this is where I train. I’ve attended countless matches and have nothing but admiration for the work of tournament director Valérie Tétreault, who has been tasked with doing deeply heroic work with minimal resources. But logistics don’t bend to good intentions. Urban density is not a suggestion; it’s a hard constraint. And no amount of passion can change that.

There are broader questions here, too—ones we as a city have to confront. What does it mean to hold onto prestige events that no longer fit our built environment? Why do we cling to legacy status when the infrastructure no longer supports it? And let’s not pretend this is a unique problem. Montreal has watched, almost in real-time, as once-iconic venues like the Olympic Stadium decayed into irrelevance. Our city, so rich in history and culture, often lags when it comes to investing in the future. With tennis, we have now arrived at the point where sentimentality is no longer enough.

It’s time to be honest: if we want Montreal to remain on the global tennis calendar, we need a new venue. Not a facelift. Not another band-aid or temporary patch job. A brand-new facility, designed with the realities of 21st-century professional tennis in mind—ample room for fan zones, practice courts, hospitality, and media; streamlined access; sustainable infrastructure; and the ability to adapt as the sport continues to evolve.

Can that happen here? Not in this neighborhood. And likely not in this city—at least not without the kind of political and financial will that has been conspicuously absent for decades. Let’s not forget that Stade IGA, one of our national tennis centers, is Stade Jarry—where the Montreal Expos once played. Why do the Expos no longer exist? A sad story for a different op-ed, but suffice it to say, there are far too many parallels between what made the Expos extinct and what the tennis world is going to see later this month.

All of this, sadly, leads to the only responsible conclusion: it’s time for Montreal to relinquish its grip on professional tennis’s top tier. As someone who is no fan of Toronto, if we’re going to have 1000-level tennis in Canada, Toronto needs to take up all of—rather than the current half of—the mantle.

Montreal can still be part of the tennis world. A 250-level event would still draw fans. Junior events and ITF tournaments thrive here—I happily watch them every year. The city’s tennis culture is remarkably strong. But the era of Montreal as a major tour stop is ending. We can either embrace that fact and plan for a graceful transition—or we can ignore it and let the sport leave us behind on its own terms.

There’s no shame in stepping aside when it’s the right time. Montreal gave the world unforgettable matches, unforgettable champions, and a uniquely intimate tennis experience. That legacy won’t be undone by acknowledging what’s plain to see: we’ve outgrown our venue, and our venue has outgrown our ability to fix it.

So let’s celebrate the players who come here this summer. Let’s fill the stands. Let’s honor the past. But let’s not kid ourselves about the future. This isn’t a pause. It’s the final set. And it’s time to let go.

Read also

Written by Aron Solomon

A Pulitzer Prize-nominated journalist for his groundbreaking op-ed in The Independent exposingthe NFL’s “race-norming” policies, Aron Solomon, JD, is a globally recognized thought leader inlaw, media, and strategy. As Chief Strategy Officer for AMPLIFY, he leverages his deep expertise to shape the future of legal marketing. Aron has taught entrepreneurship at McGill University and the University of Pennsylvania and was honored as a Fastcase 50 recipient, recognizing him among the world’s top legal innovators.

A prolific commentator on law, business, and culture, his insights regularly appear in Newsweek, The Hill, Crunchbase News, and Literary Hub. He has also been featured in The New York Times, Fast Company, Fortune, Forbes, CBS News, CNBC, USA Today, ESPN, TechCrunch, BuzzFeed, Venture Beat and countless other leading global media outlets.

claps 0visitors 0

Just In

Popular News

Latest Comments

- If WTA cared about the players they would have listened to them 2 seasons ago and NOT manufactured a grueling, demanding schedule. Basically, given WTA's demands and threats, forcing them to perform beyond the human body's normal capacity

- WOW!! Finally some extensive (correct) and intelligent insight. Word-for-word exactly what WTA offers fans/viewers -- but also what needs to do to salvage its Future. Great stuff by writer Aron Solomon!

- Ha-ha-ha... great stuff from Pegula. The important thing is, Vekic went home. Contrary to what Jess said, she is not a "nice person". Although she seems to be trying hard to change that these days.

- tennisuptodate seems to want to be a sensationalist rag like its lame competition online. Majority doesn't give a rat's ass about the Willams' personal problems and needs for the Spotlight... so stop already.

- This article is SPOT ON!!!!

- Playing against #86 was a good practice session... most work she did all month.

- Awwww.... it's always "so unfair" for these two sisters. 1. She is wasting able young players' opportunities by seeking out Wildcards she does not deserve. Retire means RETIRE. 2. Deal with the situation(s) like no immediate water, etc. -- just like everyone else.

- "He ended up saying, 'look, I don't think this is going in the way we both want it to' so he ended it really." TRANSLATION: 'If you're not going to listen, or do the work, it is over'

- Hideous pattern -- by WTA !! How many more upcoming worthy young players are going to be ignored because WTA keeps throwing away 'Wildcards' to this wealthy, bored individual??

- "It's just that I would rather someone not come in and tell me 'let's do this', and I disagree with it but have to listen to them." BINGO! There you have it -- plausible Root Of The Problem!!

Loading