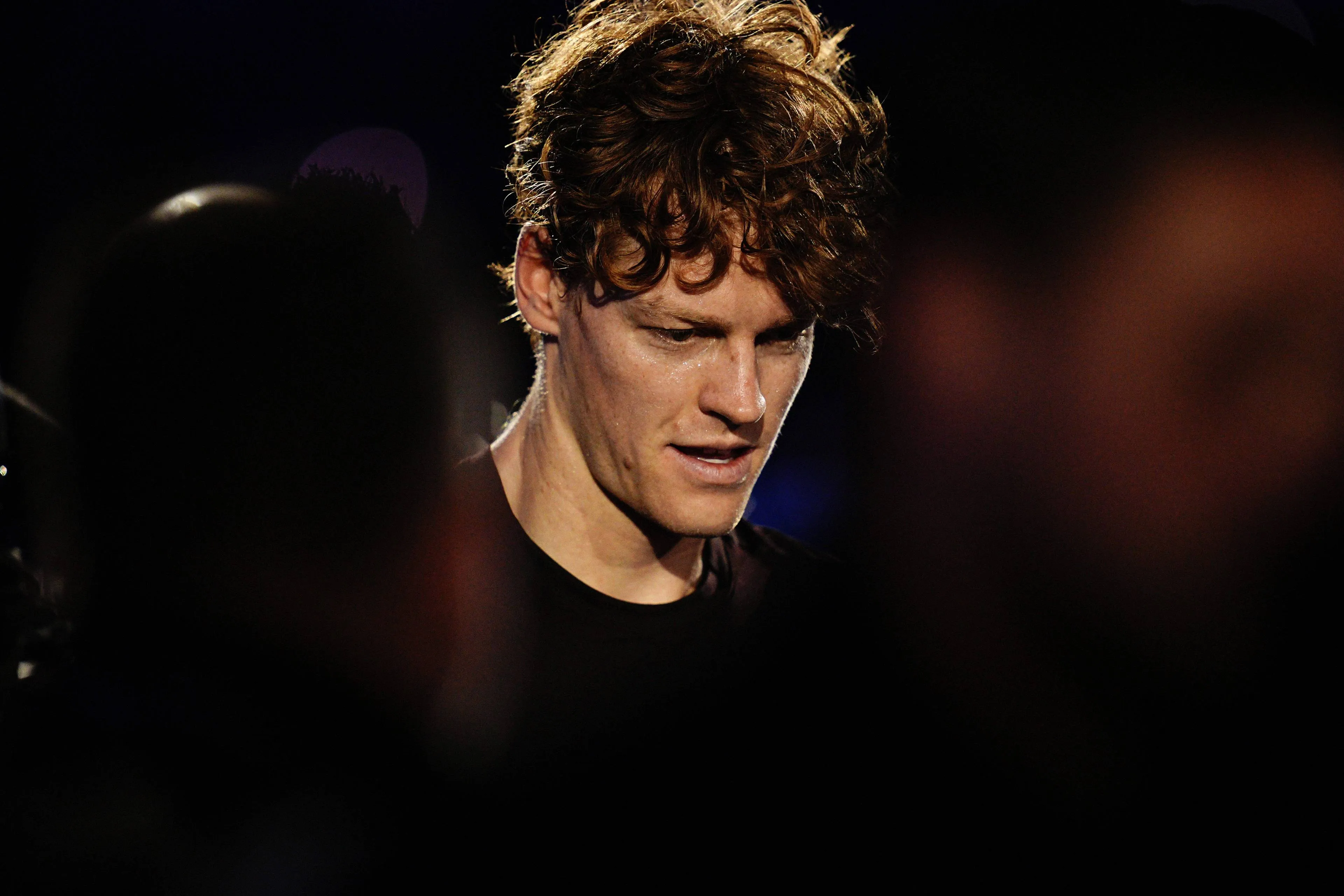

Jannik Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz receive $1.2 million each in Qatar Open participation deal

ATPTuesday, 17 February 2026 at 01:00

The 2026 Qatar Open begins this week in Doha with a field more typical of a Masters event than an ATP 500. World No. 1 Jannik Sinner and No. 2 Carlos Alcaraz lead the draw, joined by three Top 10 players, including Alexander Bublik, and a total of seven Top 20 competitors such as Daniil Medvedev, Andrey Rublev, Jakub Mensik and Karen Khachanov.

Novak Djokovic, an ambassador for Qatar Airways, had initially entered but later withdrew. Even without the 24-time Grand Slam champion, the tournament reflects the financial power of its organizers, who continue to position Doha as a premium stop on the calendar amid broader discussions about the ATP’s long-term restructuring.

At the center of this year’s conversation are the appearance fees paid to Sinner and Alcaraz. According to information from La Gazzetta dello Sport, both players are receiving approximately $1.2 million in promotional compensation, figures that significantly exceed the tournament’s official prize money for on-court performance.

The 2025 champion in Doha will collect $529,945, while the runner-up earns $285,095. By comparison, the guaranteed sums offered to the top two players underscore how financial incentives at certain ATP 500 events are reshaping the competitive and economic balance within the men’s tour.

Read also

The second seed Jannik Sinner already made his debut this Monday with a convincing victory against Tomas Machac (6-1, 6-4), taking over the Center Court during the night session. Alcaraz – first seed – will take to the court this Tuesday to face Arthur Rinderknech, also occupying the Center Court in Doha.

Promotional fees reshape the ATP 500 landscape

The ATP regulations allow 500 and 250 events to offer compensation for professional services, commonly referred to as promotional fees. These payments are justified by the commercial appeal of elite players. In practical terms, the greater the marketing value, the higher the compensation negotiated between tournament organizers and players’ teams.

In Doha, that mechanism has been used aggressively. According to Gazzetta, while leading players typically command between $800,000 and $1 million for such appearances, Qatar’s financial capacity has pushed that figure higher. As one industry source noted, “the purchasing power of the Qataris favors an increase,” reflecting a willingness to outbid competitors.

This investment aligns with Qatar’s broader sports strategy. The country has been present on the ATP Tour since 1993, gradually upgrading its event from 250 to 500 status and increasing prize money from $1.4 million to $2.8 million in 2025. Former champions in Doha include Stefan Edberg, Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, Andy Murray and Djokovic, reinforcing its prestige.

Read also

Ranking rules add pressure for top players

The financial dimension intersects this season with significant changes to the ATP ranking system. The 52-week ranking basket has been reduced from 19 to 18 tournaments, plus the ATP Finals. Meanwhile, the number of mandatory ATP 500 appearances has been cut from five to four, with one required after the US Open for so-called “committed players.”

These “committed players” are those who finished the previous season inside the Top 30. Withdrawing from a mandatory 500 now results in a zero-point penalty in the rankings, except in cases of long-term injury. That zero can be offset only once per season by playing an additional 500 event during the calendar year, bringing the total to four.

Participation also impacts eligibility for the year-end bonus pool, which distributes $3.1 million based on results in 500 events. Last year, Alcaraz earned $1.2 million from that fund, while Sinner received nothing after competing in only three ATP 500 tournaments. The financial calculus, therefore, extends beyond appearance fees and into ranking strategy.

As ATP President Andrea Gaudenzi explores plans for a more “premium” circuit by 2028, potentially centered around Masters events and including a Saudi Arabian stop, smaller tournaments are watching closely. Some fear marginalization, while others, backed by substantial state investment like Doha, appear determined not only to survive but to push toward 1000-level status.

Read also

claps 0visitors 0

Just In

Popular News

Latest Comments

- The poor Head Sportswasher has been whining and crying in the media, and basically threatening Saba, Iga, etc. Must be a real Ego Buster when they dangle money and people (especially Women) say, 'No thanks'.

- "Losing-itis" is not uncommon in Emma's small world. Just keeps begging the question, 'What are sponsors paying for? Limited tennis appearances... or Social Selfie Media presence?'

- Dubai can suck it up like everyone else. Just because they think they run the show, they do not. Sportswashing does not give them Power.

- You're losing your mind here.. You use a lot of space, yet inadequate knowledge. Read the WTA Rule Book 2026; it answers all your questions and accusations.

- Why single out Iga and Aryna to punish?, Since when do players get punish because they withdraw from tournaments? Maybe if they both were treated like number one and two players, they would not have this problem. The WTA discriminates against them because of their nationalities, yet they want to make money off them. Every tournament, Iga has harder draws than qualifiers from the beginning to the end. In the Australian Open they stuck Aryna out in the sun the majority of her matches in order to tire her out. She is the number one player in the world and she never got the opportunity to play with the roof closed. If they want these top players to continue playing and making money for them, then they should treat them as such. Otherwise, get the players who they are always giving out cupcake draws to like Pegula to play their tournaments. Lets see how many seats in the audience she will fill. Iga has more fans in the seats than any player in the WTA, yet she is always disrespected and mistreated because of her nationality. The WTA is a corrupt, bias and racist organization. No matter what job someone is on, you cannot tell them that they are not sick or injured.

- LOL. Billie Jean King hates being a woman.

- Pulling out a tournament is not illegal. Therefore, that is no problem. Maybe they need more rest.

- It is simple. If you do not want cameras following you, get away from tennis and go find another job. Cameras and interviews are a part of the job. They do not mind cameras when they are winning. If the women tennis players would put the same amount energy to playing tennis as they do with complaints, women tennis would be exciting to watch.

- Yeah, that's what I would do... be nice and lose a match

- Turns out Swiatek is as big a cheater as Draper (remember vs FAA?)when she didn’t admit to hitting a double bounce drop shot. The blind chair ump didn't even see it on the replay but fortunately got the correct call from someone on the phone (supervisor?) we all saw it…..it wasn’t even a close call. Great win Sakkari !!

Loading