Tennis Legends - Suzanne Lenglen: The first global superstar of tennis credited with Grand Slam move

WTAFriday, 14 November 2025 at 17:08

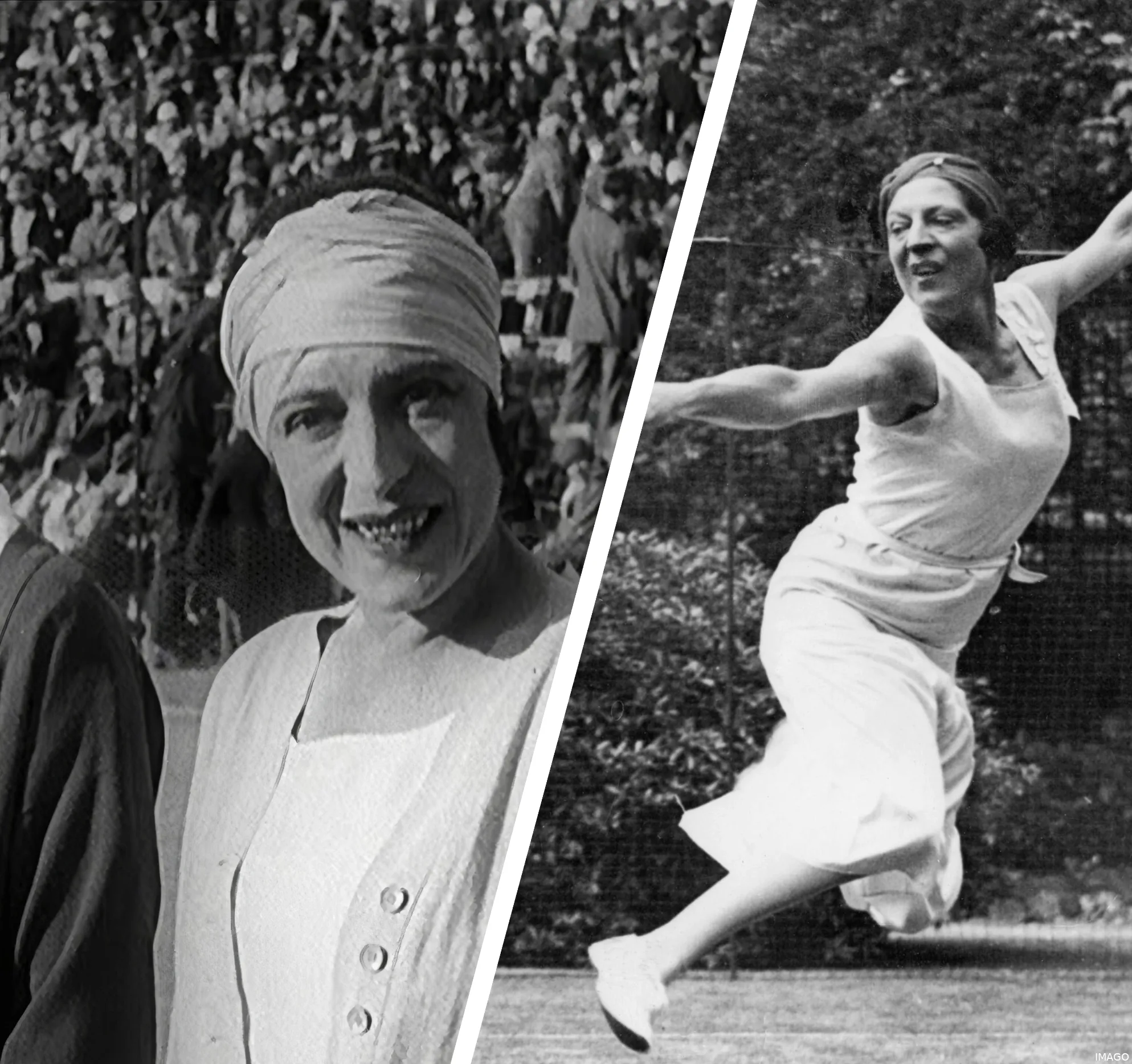

Suzanne Lenglen was the first global superstar of tennis. Her popularity is cited as a factor in Wimbledon moving from its original Walpole Road home to a much greater site at its current home of the All England Club.

Suzanne Lenglen: Early life and the rise of 'La Divine'

Born in the French capital, Paris, on May 24, 1899, to parents Charles and Anais. Her younger brother tragically died as a toddler. After her father inherited a horse-drawn omnibus company from his dad, the family relocated to Nice on the French Riviera. They were in close proximity to the Nice Lawn Tennis Club. Lenglen became talented across many sports, including diabolo, a game involving balancing a spinning top on a string with two attached sticks. Her father believed this helped his daughter play with greater confidence due to performing in front of crowds as a diabolo performer. It was her father who would train Lenglen at tennis, and she was soon having success.

Aged only 13, Lenglen picked up her first title at the Picardy Tournament in Compiegne, France. A couple of additional titles were secured in Wimereux and La Touquet. The following year witnessed even greater success as the Parisien lifted five titles, including the prestigious World Hardcourt Championships title. This period of teenage success was abruptly halted with the outbreak of World War One. Lenglen’s career was now on hold until hostilities ceased in 1919.

When tennis resumed after the war, Lenglen began to dominate and was close to unplayable for the six years. This was still very much the amateur era of tennis, where limitations in travel led to fields far less international than today. Until 1922, the Challenge Round system (which enabled the defending Grand Slam champion to only have to play the final to retain their title) was a situation which made it easier to dominate. Nevertheless, very few can match Lenglen in the amateur era for such a dynasty and volume of success.

Read also

Dominance at Wimbledon and the Olympics

In 1919, Lenglen won nine of the ten singles events she entered. She remarkably didn't concede a single game across four matches to win the South of France Championships. This year saw Lenglen make her debut at Wimbledon. The Frenchwoman had to navigate her way through six rounds to achieve an opportunity of dethroning the current 7-time champion Dorothea Lambert Chambers. The final was an all-time classic as Lenglen prevailed 9-7 in an epic three-set contest lasting a then record 44 games. Lenglen was twenty years Chambers' junior. A first Grand Slam victory proved to be the catalyst for a run of five consecutive Wimbledon triumphs.

The 1920 campaign saw Lenglen become untouchable, winning 13 titles, including defending her Wimbledon crown. In a repeat of the previous year's final, Lenglen destroyed Chambers 6-3, 6-0. Other titles claimed this term included the French Championships - a forerunner of the French Open - which lacked Grand Slam status as it was only open to players assigned to French tennis clubs. In August, Lenglen accomplished a ‘triple crown’ at the Antwerp Olympics. Lenglen won the singles, doubles and mixed doubles gold medals.

Lenglen's 1921 campaign yielded ten titles, including retention of her Wimbledon and French Championships titles. In an effort to underline her status as a world champion, Lenglen attended the US National Championships (now the US Open). In round two, scheduled to play the American star Molla Mallory, who won eight US titles, she fell sick in the lead up to the match. Mallory took the first set before Lenglen retired 2-0 down in the second set. This represented, extraordinarily, Lenglen’s only singles defeat after WW1.

A mammoth 179-match winning streak commenced when Lenglen returned in March 1922 to reassert her dominance. This run lasted right through until she called time on her amateur career. The year saw triple crowns secured at Wimbledon, the World Hardcourt Championships and the French Championships. Lenglen took revenge on Mallory in the Wimbledon final, defeating her in just 26 minutes. This remains the shortest final in Wimbledon history.

From unbeatable to plagued by injury

Her 1923 season reached even greater heights. All 16 singles events she entered were won. This included a triumph at the final edition of the World Hardcourt Championships.

The year 1924 would develop into an injury-plagued year for the French stylist. A limited schedule in the Riviera saw her only play three singles events, winning them all. A victory soon followed at the Barcelona International, but she also, on her return, contracted jaundice. At Wimbledon, she unusually had to work harder to progress. In round four, Lenglen dropped a set to Elizabeth Ryan - only the third set she'd lost since WW1 - before edging the deciding set. However, on the doctor's advice, she withdrew from the tournament, denying her the chance of a sixth Wimbledon title in a row. The illness forced arguably even greater disappointment when she missed an opportunity to compete at her home Olympics in Paris later that summer.

Eight titles in 1925 included the French Championships - now considered a Grand Slam - and the last of her six Wimbledon titles. These two singles victories were supplemented by triumphs in the doubles and mixed doubles at both majors. Later in the year, making her only career appearance in England outside Wimbledon, Lenglen won the doubles and mixed doubles at the Cromer Covered Courts Championships.

The professional move that changed tennis forever

The 1926 campaign would prove to be the last for Lenglen on the amateur scene. It was a season remembered best for a match dubbed the ‘Match of the Century’ between Lenglen and the three time US champion Helen Wills (later Wills Moody) who was beginning to rival Lenglen's profile. Wills was keen to visit the French Riviera and challenge the supremacy of Lenglen. In the only singles tournament both entered, the Carlton Club in Cannes, would bear witness to a final between the tennis titans of the age. The interest generated by this match resulted in the venue doubling the number of seats available and a number watched from trees and other elevated vantage points. The victory went to Lenglen in a tight three-set contest. However, Lenglen’s reputation as being unbeatable was now under threat by how close Wills came to beating her. The American stayed in the Riviera, but Lenglen never accepted a rematch. This iconic contest unfortunately never acted as a catalyst for a rivalry that could've potentially challenged Evert/Navratilova as the sport’s greatest.

The reason they never met again was Lenglen’s decision later in 1926 to quit amateur tennis and turn professional, thus denying her any further opportunity to enhance a tally of eight Grand Slam singles titles. At Wimbledon that year, in what proved to be her last Slam, Lenglen became disillusioned with her treatment after her singles match was moved to accommodate a visit from Queen Mary. She then kept her waiting, and this led to the crowd turning against her. She was still involved in both the singles and mixed doubles before sensationally withdrawing. The French Championship, won a month earlier, would turn out to be her last Grand Slam success.

A month later, Lenglen would sign a contract worth 50,000 dollars with US promoter C.C.Pyle. She'd previously turned down professional offers, but her sour Wimbledon experience triggered the switch. The pro circuit lacked top players, though, and Lenglen was part of a small number that toured on an exhibition circuit of 40 stops. The problem was that her only opponent was the unheralded Mary Browne. It took until their 33rd match for Browne to even win a set! A shorter British tour followed in 1927. These events were lucrative and well attended.

Read also

Lenglen drew stinging criticism for her decision to turn professional. Her membership at the All England Club was revoked. The Paris native defended herself in response to her growing critics: “In the twelve years I have been champion I have earned literally millions of francs for tennis ... And in my whole lifetime I have not earned $5,000 – not one cent of that by my specialty, my life study – tennis ... I am twenty-seven and not wealthy – should I embark on any other career and leave the one for which I have what people call genius? Or should I smile at the prospect of actual poverty and continue to earn a fortune – for whom?" Lenglen went on to launch a diatribe over the lack of earning opportunity and incentives for more to see tennis as a career: "Under these absurd and antiquated amateur rulings, only a wealthy person can compete, and the fact of the matter is that only wealthy people do compete. Is that fair? Does it advance the sport?” It wasn't until just over four decades later that the sport would become fully open, and amateurs combined with the pros could enter the Grand Slams at the same time.

Across doubles and mixed doubles, Lenglen claimed 167 titles. This included 12 Grand Slam titles (seven in doubles and five in mixed). The majority of her women's doubles success was with American Elizabeth Ryan.

Personal life - author and health issues

Her primary romantic entanglement was with US businessman Baldwin Baldwin. He was a married man and his wife refused to grant a divorce so they could marry.

Lenglen authored many tennis books. Amongst the literature was a romantic novel, "The Love Game: Being the Life Story of Marcelle Penrose". She also made an appearance in the film comedy "Things Are Looking Up", portraying a tennis player.

The 8-time Grand Slam singles champion eventually moved into coaching. In 1936, Lenglen opened up a tennis school at Tennis Mirabeau in Paris. Two years later, she was appointed as the first director of the French National Tennis School.

Health issues began to plague her as the 1930s moved on. She underwent an appendectomy in October 1934. On the July 4, 1938, Lenglen died from what was reported at Pernicious Anaemia. She was only 39.

Lenglen was the first player to transcend the sport. The crowds that flocked to her matches were evidence of her pulling power. Her dominance was extreme, including winning nine singles tournaments without losing a game. She was a trailblazer. Firstly, Lenglen was a fashion pioneer. Her decision to play in attire more fitting for athletic endeavour was a game-changer. Lenglen enlisted Jean Patou to design an outfit that allowed her to execute her signature leaping ballet motion in points and give her greater flexibility when moving around the court. Lenglen was also the first player to turn professional. This was unfortunate for spectators, denied a great rivalry with Helen Wills, and stopped Lenglen from adding to the Octet of majors. Despite her career being interrupted by this call and WW1, Lenglen is still the French tennis GOAT. The women's singles trophy at the French Open is named after her, as is the second showcourt at Roland Garros. Lenglen’s life was short, but she packed so much into becoming the maiden global tennis icon.

Read also

Suzanne Lenglen: Career Titles and Major Achievements

| Category | Achievement | Details |

| Grand Slam Singles | 8 | Wimbledon (6), French Championships (2) |

| Grand Slam Doubles | 21 | 8 Women's Doubles, 13 Mixed Doubles |

| Olympic Medals | 3 | Gold (Singles & Mixed), Bronze (Doubles) — 1920 Antwerp |

| Career Win % | 98% | Lost only 7 matches in her entire career (Singles) |

| Winning Streak | 181 Matches | Unbeaten between 1919 and 1926 |

| World No. 1 | 1921–1926 | Ranked as the undisputed best in the world for six years |

| Wimbledon Record | Triple Crown | Won Singles, Doubles, and Mixed in 1920, 1922, and 1925 |

| Court Dedication | Roland Garros | The second show court in Paris is named "Court Suzanne Lenglen" |

Suzanne Lenglen: Major Finals and Milestones

| Year | Competition / Tournament | Result | Category |

| 1914 | World Hard Court Chp. | Winner | 1st major title at age 15 (Youngest Major winner) |

| 1919 | Wimbledon | Winner | 1st Wimbledon Title (Defeated Dorothea Lambert Chambers) |

| 1920 | Antwerp Olympics | Gold Medal | Won Gold in Singles losing only 4 games total |

| 1920 | French Championships | Winner | 1st domestic Major title in Paris |

| 1921 | Wimbledon | Winner | Defeated Elizabeth Ryan in a dominant final |

| 1922 | Wimbledon | Winner | Won Singles, Doubles, and Mixed (Triple Crown) |

| 1923 | French Championships | Winner | 2nd French Singles title |

| 1925 | French Championships | Winner | 1st title after tournament went "International" |

| 1925 | Wimbledon | Winner | Lost only 5 games across the entire tournament |

| 1926 | "Match of the Century" | Winner | Defeated Helen Wills in their only encounter (Cannes) |

| 1926 | Professional Tour | Pioneer | Became the first high-profile player to turn professional |

claps 0visitors 0

Just In

Popular News

Latest Comments

- All those whom believed they could accept the Sportswasher's money and free housing and still maintain their Freedoms -- how's that going over there at the moment? Not too good??

- Issues much? Why is this story not going away??

- Could they hear the bombing in the background? I imagine the tennis players/teams "living" in Dubai and Doha might be selling their apartments for an excellent price in the very near future... such as it is!!

- Who gives a rat's ass??

- This person has arguably always been a 'problem personality'. Rarely, if ever, has he been The Solution to any matter in sports. More often combative and accusatory via media blurbs and texts. As for his "great success" as a coach -- the planets were aligned in his favor the day The Williams Family signed on to him. The William sisters were going to succeed regardless of his, or anyone else's, input. If you want to know how other players' have been affected by his "coaching" simply study the graphics on a chart. Average results, with a degree of combativeness and animosity in every camp. His "success" is entirely attributed to the natural Williams talent(s). Not unlike Raducanu's claim to fame of winning one title.

- Quinwen learned it's better to have friends in tennis. Happy to see she has changed her attitude on the circuit.

- Remind her the racquet is in HER hand, not any coach.

- My advice to Coco is take a few months off from the tour and focus on the serve. If MacMillan is not producing the expected results, relieve him of his duties and hire someone else. To hell with the rankings and what people will say. Just take a break. Mental health is far more important than money.

- Eventually (as other sports have done) WTA will be forced to make DNA / Gender Testing mandatory in order to protect and promote fairness in competitions. End of so-called 'controversy'.

- It's sad... but Rybakina is not going to be able to endure her groomer's interference in Life and still excel to her best level. BTW: No media has reported her last sentence to the physio. They kept asking questions and she abruptly told them: "I know what it is; I'm ready to go now".

Loading