"I was the closest to quitting I’ve ever been": How freedom and friendship unlocked Brit Francesca Jones's best year after near retirement

WTAWednesday, 17 December 2025 at 13:00

By the end of last season, Francesca Jones was closer to quitting tennis than she had ever been. Not because she lacked belief in her ability, or because she felt she didn’t belong at that level — but because her body, and the constant fight against it, had worn her down.

“I questioned myself a lot,” Jones admitted to Tennis Insider Club. “I still do. Anyone who tells you they don’t have self-doubt is hiding behind a façade. It’s not realistic.”

For Jones, doubt was never about tennis IQ or shot-making. It was physical. Always physical. “I knew I had tennis ability. I felt like my game was good enough to be there. But the physical side just wasn’t backing me up for so long.”

Living on the edge of retirement

The numbers told a strange story. Jones played around 15 tournaments last year. She retired from seven of them. Yet despite that, she still finished the season ranked around 140. “People were telling me 140 isn’t a great number, which I get,” she says. “But when you put it into context, it was still quite a solid effort.”

What hurt most wasn’t the ranking — it was seeing those retirements pile up next to her name. “When I was a kid, I used to say I’d never retire. I’d die on court. You’d never see me retire,” she says, laughing at her younger self. “I’m learning how unrealistic that was.” By the end of the year, the thought of walking away no longer felt dramatic. It felt possible. “I was the closest to quitting I’ve ever been.”

The Physical fight that never left

Jones’ relationship with tennis has always been shaped by limitation and adaptation. She learned early that survival at the highest level meant thinking the game differently. “I’ve had to think of tennis from such a tactical standpoint,” she explains. “Because of the lack of physicality, I either understood how to play the player or I had no chance.”

That tactical sharpness kept her alive in matches, but when the body didn’t follow, frustration crept in. “I can suffer on court for as long as I need to suffer,” she says. “Hours, matches, weeks — that part doesn’t bother me.”

Read also

Nadia Podoroska and the decision to keep going

At the moment Jones was closest to stopping, one relationship anchored her. “Nadia Podoroska was a big reason why I kept going,” she says without hesitation.

Jones spent two weeks of her pre-season with Podoroska, splitting time between training and stepping away mentally. She gave herself space — not just from tennis, but from the identity that had consumed her. She remembers hiking in Patagonia and meeting a woman who had no idea what tennis was. "We just spoke about life,” Jones says. “I needed those wholesome moments.”

She’s quick to dismiss the idea of a cinematic turning point. “That woman didn’t change my life,” she says. “But those experiences, and having someone older than me on tour — who I love reminding is older than me — talking honestly about the barriers she’s had to overcome, really helped.”

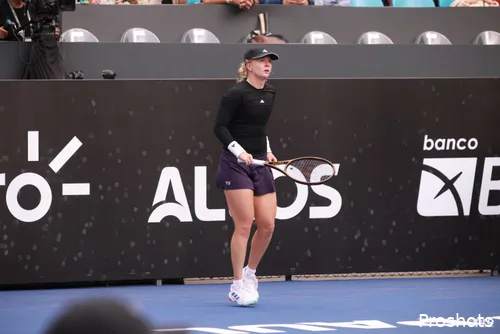

Francesca Jones in Sao Paolo.

The ‘What If’ that changed everything

Jones realised that fear had always shaped her thinking — particularly the fear of losing momentum. “I’m very much a ‘what if?’ thinker,” she admits. “Normally it comes from a negative place.” But as retirement loomed, she flipped the question. “What if it works? What if you do it?” she asked herself. “How are you going to feel then?”

That mindset led to a drastic internal decision. "At the start of this year, I said this was going to be my last year on tour,” Jones reveals. “If I didn’t finish the year inside the top 100, I was done.”

Instead of creating pressure, it created freedom. “I don’t know if that detachment from what I needed to be is actually what helped me have a solid year.”

Obsession, professionalism and burnout

Jones has always prided herself on professionalism — but over time, it morphed into obsession. “I was obsessed with doing everything right,” she says. “GPS numbers, calories, kilometres covered, changes of direction.” She would question her team constantly. “Have I moved enough? Have I done enough? Did I burn enough calories?”

She recognises now how quickly that mindset can burn an athlete out. “This year, when I’m on court, I’m obsessed. But off court, I’m trying to wind it back.”

Learning how to juggle work and life

For most of her career, Jones viewed anything outside tennis as a threat. “I used to think concerts or going out would jeopardise my career,” she says. “I didn’t drink alcohol until I was 21 — and even then, I’d panic.” This season, she’s experimenting with balance — cautiously. “Last night in New York, I went out and had two cocktails,” she says. “I’m trying to allow myself to live, without crossing the line.”

The same evolution happened with food. After strict diets and intolerances made life miserable, Jones changed approach. “Now I eat what I want,” she says. “I’m in the best weight I’ve ever been in. I don’t have more injuries. My mind is in a way better place.” Her philosophy is simple. “Optimising is cool. But if it costs you being miserable, it’s not worth it.”

When ‘more’ isn’t better

Even now, Jones admits she struggles to accept rest. “There are days when I’m exhausted, but I think maybe two extra sets will make the difference.” A defining moment came when her strength and conditioning coach, Steve, refused to join her for an extra bike session. “He told me I could go, but he wasn’t coming because I shouldn’t be doing it,” she recalls. “If the guy whose job it is to train me is saying no, then I’m probably getting something wrong.”

She’s still learning the lesson. “More doesn’t always mean better. Sometimes less really is more.” Despite her progress, Jones hasn’t fully absorbed how close she came to leaving the sport. “I don’t think I’ve processed this year yet,” she admits. “Maybe when the season ends.”

Even moments away from tennis don’t fully disconnect her. “I went to Ibiza for a weekend, and even then I was thinking about the US Open.” But she no longer sees that as failure. “That’s the balance. You can go away and still care about your work.”

Breaking into the top 100 was once a line in the sand. Now, it’s simply part of a bigger picture. “My priority is playing a full season,” Jones says. “If I can back this year up with another full year, that’s huge for me.” She avoids ranking obsession. “Top 50 is a milestone, but I don’t think it’s the right way to think. I just want to keep getting better.”

Moments like playing childhood rivals on the biggest stages reinforce how far she’s come. “It was a full-circle moment,” she says of facing Diana Shnaider in Madrid. “I finally felt like I was back playing the people I wanted to play.”

Read also

The relationships that saved her

Jones speaks openly about the importance of connection on tour — something she once believed was forbidden. “My relationship with Nadia is arguably the most important in my life,” she says. “Not just my career.”

She also shares a close bond with Emma Raducanu who she previously said she spoke to every single day, built on honesty and vulnerability. “Why hide it?” Jones asks. “It’s unrealistic to pretend we don’t struggle.”

She believes the culture in women’s tennis is changing. “I think the newer generation is more open with each other and that’s what women’s tennis needed.”

Last year, Francesca Jones was preparing herself to walk away. This year, she’s learning how to stay, not by forcing more, but by letting go. “I’m still learning,” she says. “But I’ve made that change this year, for sure.”

For a player who once believed quitting meant failure, survival has taken on a new meaning. Not just staying on tour — but staying whole.

claps 1visitors 1

Just In

Popular News

Latest Comments

- Rybakina could have finished that guy off... but he tucked his tail and quit.

- Williams still stealing and wasting some young player's opportunity. Gross injustice.

- She blames the conditions for her loss but her opponent had to play in the same conditions. To me, this means she is belittling the abilities of her opponent. She lost to a player who played better.

- I will talk to her soon. My girl cannot stomach tiebreak losses anymore.

- If WTA cared about the players they would have listened to them 2 seasons ago and NOT manufactured a grueling, demanding schedule. Basically, given WTA's demands and threats, forcing them to perform beyond the human body's normal capacity

- WOW!! Finally some extensive (correct) and intelligent insight. Word-for-word exactly what WTA offers fans/viewers -- but also what needs to do to salvage its Future. Great stuff by writer Aron Solomon!

- Ha-ha-ha... great stuff from Pegula. The important thing is, Vekic went home. Contrary to what Jess said, she is not a "nice person". Although she seems to be trying hard to change that these days.

- tennisuptodate seems to want to be a sensationalist rag like its lame competition online. Majority doesn't give a rat's ass about the Willams' personal problems and needs for the Spotlight... so stop already.

- This article is SPOT ON!!!!

- Playing against #86 was a good practice session... most work she did all month.

Loading