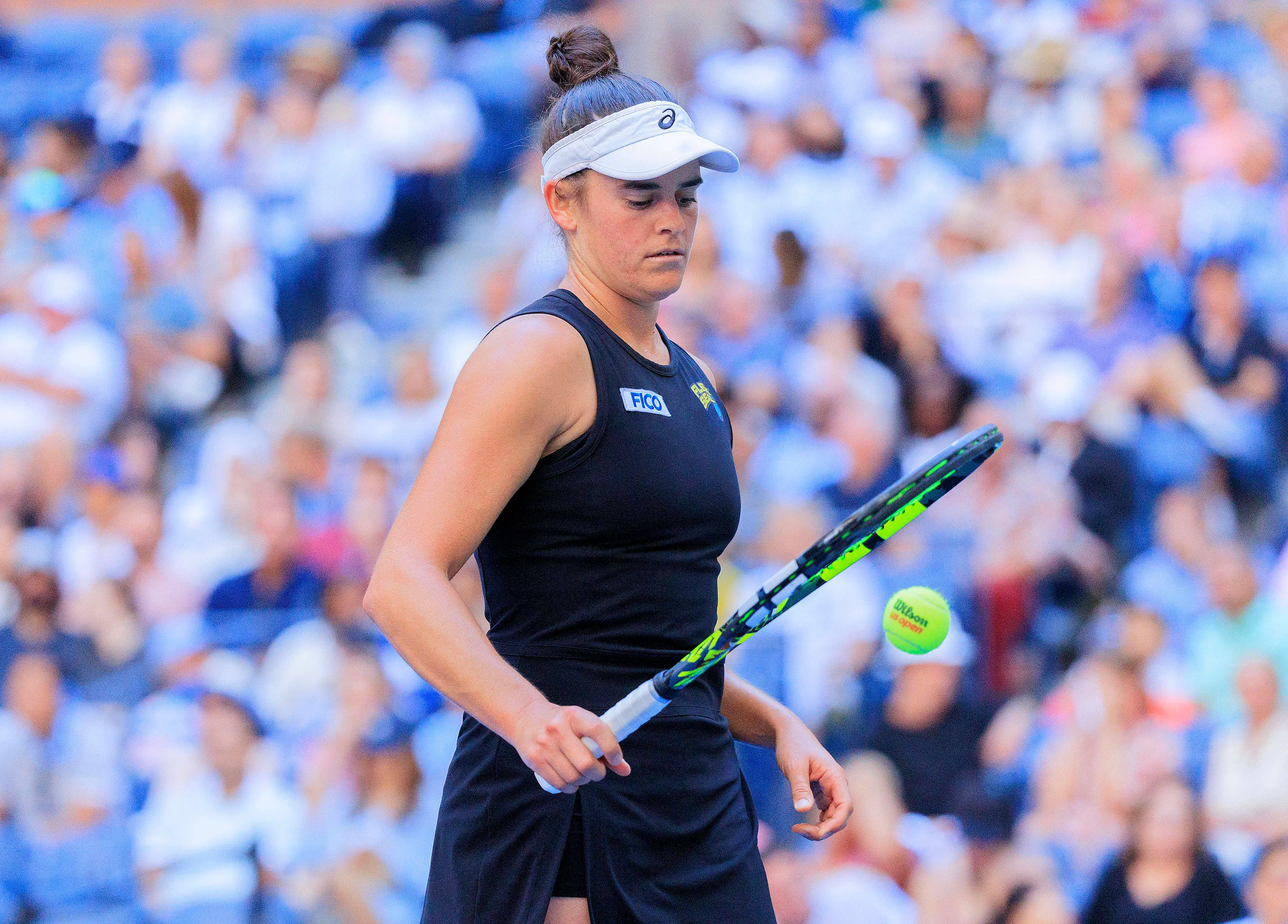

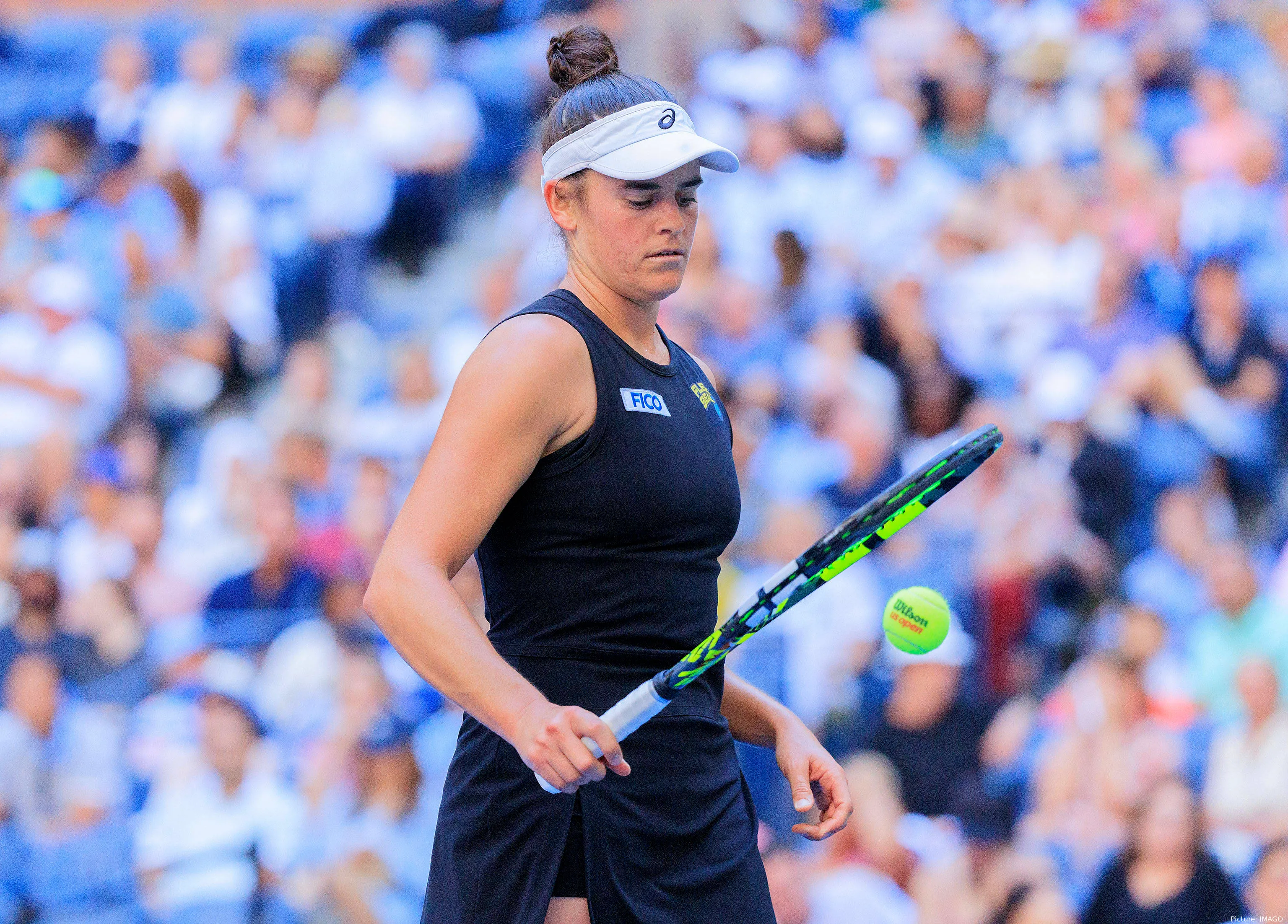

"You get to a point where you’re like, will I ever be able to play again?": Using a dead person's knee to comeback doubts as Jennifer Brady makes lower level return

WTATuesday, 03 February 2026 at 13:30

For the first time in years, Jennifer Brady is edging back toward the tennis court with competitive intent. The former Australian Open finalist has spent much of the last three seasons away from the tour, battling a serious knee injury that required major surgery and tested her both physically and mentally.

Speaking on the Changeover Podcast, Brady opened up in detail about what went wrong, how dark the recovery became at times, and why her recent return means so much.

“Back in 2023 – well, actually, yeah, 2023 – I had a knee injury, and I was playing with it for a little while, like putting a Band‑Aid on it, you know?” Brady explained. “And then it just kind of got to a point where I couldn’t really play the way that I wanted to play or train the way that I wanted to train.”

With conservative treatment no longer an option, Brady was left facing a daunting solution. “So the only option was to do a pretty large surgery,” she said. “I had to do a cadaver transplant in my knee.”

The procedure, as she admitted, was something she barely understood until she was living through it herself. “They basically take cartilage from someone who obviously is dead – so a cadaver,” Brady said. “They take cartilage, they have to test it and stuff, and then they put it inside.”

Read also

Using dead person's knee for surgery

The surgery was required to repair a literal hole in her knee joint. “I had a spot in my knee that it was like there was a hole in the joint,” she explained. “So I needed to fill it with cartilage.” While using her own cartilage was an option, Brady opted against it. “I was like, watch my luck – they’ll end up taking it from somewhere and then I’ll end up having symptoms and need another transplant.”

Instead, donor cartilage was used, but even that came with an uncomfortable waiting period. “I was calling the doctor’s office and I was like, ‘Hey, I need to get in for this. I’ve been waiting several weeks,’” she recalled. “And the woman was like, ‘Well, I don’t know if you know this or not, but someone has to die in order for you to have your surgery.’ I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, yeah, I know.’”

Brady eventually underwent surgery in February 2024. The recovery was long and unforgiving. “It was eight to ten weeks non‑weight bearing on crutches,” she said. “It was pretty brutal. It sucked a lot.” By that point, she hadn’t competed since October 2023.

Physically, the aftermath was shocking. “I lost a lot of strength,” Brady admitted. “That’s the toughest part to get back. I was wilting away. My legs had no lower‑body strength at all. It’s so crazy how quickly you lose it and how long it takes to build back up.”

Her return to the court came in frustrating bursts, often followed by setbacks. “There were periods where I wasn’t even entertaining the idea of getting back on,” she said. “I had to start from zero multiple times – 15 minutes of feeding, 15 minutes of live ball, then 30 minutes, 45 minutes – that whole progression. Then you get off court and you have to do it again.”

Mentally, the process was even harder. “The unknown is probably the scariest part,” Brady said. “You get to a point where you’re like, will I ever be able to play again? Will I be able to train the way that I want to train to compete at the highest level?”

Read also

Comeback doubts

She admitted there were moments when the idea of never returning felt real. “Someone can tell you, ‘In a year, you’ll be back playing,’ and then it’s been a year, it’s been two years, and you’re still not playing yet,” she said. “For a little while, I was starting to feel like I didn’t get the chance to end on my own terms.”

That mental strain explains why Brady went quiet during parts of her recovery. “When you texted me, I was going through one of those moments,” she said. “I just wasn’t in a space to really talk. It wasn’t personal. It wasn’t cool of me to not respond, but once I got in a better place, I was like, ‘Oh shit, I need to reach back.’”

Away from competition, Brady found new outlets. One of them was podcasting. “For a couple of years, the four of us were joking about it,” she said. “Then podcasts started popping off, and it was like, ‘Oh wow, this could be cool.’ I’ve really enjoyed doing it.”

She was quick to admit she leaves the technical side to others. “Even just opening Riverside is a little bit of a challenge for me,” Brady laughed. “I’m not going to be editing any videos anytime soon.”

Perhaps more unexpectedly, Brady also rediscovered herself through coaching. Throughout 2024, she returned to UCLA, where she studied and served as a volunteer assistant coach for the women’s team. “I actually really enjoyed that – coaching and that side of things,” she said.

Asked if she could see coaching in her future, Brady didn’t hesitate. “Yeah, I definitely want to get into coaching when I’m done playing,” she said. “I don’t know about on tour – it has to be the right person, with all the travelling.”

The timing of Brady’s injury made everything harder to accept. Knee issues first surfaced toward the end of 2021, the same season she reached the Australian Open final and established herself as a genuine Grand Slam contender. “That year I was dealing with foot issues and knee issues,” she said. “I played a limited schedule, skipped the grass, and played through some pain on clay.”

By the US Open, the knee became unavoidable. “That’s where I really started to feel it,” Brady recalled. She was scheduled to face a then‑qualifier Emma Raducanu in the first round. “She ended up winning the tournament,” Brady said. Watching from the sidelines only amplified the frustration.

“That was probably the toughest part,” she admitted. “When you’re making semis and finals of Slams, it’s like, ‘Oh wow, I’m pretty decent at this sport. Maybe I could do better. Maybe I could win a Slam.’ And then you’re just sitting on the couch watching other people compete.”

She acknowledged the conflicting emotions that come with that position. “You’re happy for your friends, but there’s also jealousy,” Brady said. “It’s natural. You’re like, ‘Wow, maybe I could be doing that.’”

Now, however, Brady is cautiously optimistic. She returned to training in Orlando at the USTA and planned her comeback through ITF events, focusing on rebuilding match fitness rather than rushing expectations.

Since recording the podcast, that approach has already delivered encouragement. In her first tournament back, Jennifer Brady reached the semi‑finals – a significant milestone after years defined by surgery, setbacks and uncertainty.

After everything she has endured, the result mattered. But more than that, simply being back on court, competing again, has restored something she feared she might have lost forever: the chance to write the ending on her own terms.

Read also

claps 0visitors 0

Just In

Popular News

Latest Comments

- Quinwen learned it's better to have friends in tennis. Happy to see she has changed her attitude on the circuit.

- Remind her the racquet is in HER hand, not any coach.

- My advice to Coco is take a few months off from the tour and focus on the serve. If MacMillan is not producing the expected results, relieve him of his duties and hire someone else. To hell with the rankings and what people will say. Just take a break. Mental health is far more important than money.

- Eventually (as other sports have done) WTA will be forced to make DNA / Gender Testing mandatory in order to protect and promote fairness in competitions. End of so-called 'controversy'.

- It's sad... but Rybakina is not going to be able to endure her groomer's interference in Life and still excel to her best level. BTW: No media has reported her last sentence to the physio. They kept asking questions and she abruptly told them: "I know what it is; I'm ready to go now".

- You seem to have 'lost the plot' ??

- This needs to be done, and I think Jessica Pegula is an excellent choice for chair to look into the situation. However, a very brief look at the other members of the panel would suggest a very USA heavy contingent. The group needs to represent all interests, not just turn it into a way the US can screw more money out of an already biased calendar.

- The tennis world should be kissing her feet for taking-on this long needed position in a much needed council. The WTA and ATP need a good shaking-up. Pegula's business heritage is a proven one. Let's hope she and her colleagues can stop WTA & ATP from shutting their work down and out. GO GET 'EM !!

- So the Sportswasher's largest market is... the Filipino community? That's all well and good but the hundreds and hundreds of empty seats throughout is embarrassing. Talk about bad optics!

- The poor Head Sportswasher has been whining and crying in the media, and basically threatening Saba, Iga, etc. Must be a real Ego Buster when they dangle money and people (especially Women) say, 'No thanks'.

Loading